A museum director and a cultural strategist ask how museums can benefit from the A.I. revolution.

On the fourth day of this year’s Museums of Tomorrow Roundtable (MTR)—a biannual gathering of international museum directors in San Francisco—20 participants filed into a demonstration room at NVIDIA’s headquarters, in Santa Clara. Before us stood what looked like a space-age sculpture: a stack of chips arrayed into a tower of light and steel. This was the beating heart of the A.I. revolution, the raw muscle behind today’s large language models (LLMs).

“How long,” one of us wondered aloud, “until you reach one thousand times this computing capacity?” Our host replied matter-of-factly, “Oh, about two to three years.”

Later that morning we sat down in a classroom to learn about new applications enabled by this fast-moving technology. Eike Schmidt, director of the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, was ready with his question, which he had already posed at other tech companies on our tour, including Salesforce and Anthropic. He wanted to know if A.I. could be trained to speak in international sign language. This would be an extraordinary feat of computing, given the nuances of sign language and the difficulty of animating moving hands. It would fill a gap so significant for museums and for society, Schmidt said, that he had considered launching his own start-up to fill the void.

The data scientists of NVIDIA—which, as most of us had just learned, was a software company as much as a hardware behemoth—broke into a smile: “We’re already working on that.”

On stage at the Museums of Tomorrow 2025. Photo courtesy of Bloomberg.

It’s hard to overstate just how much the A.I. landscape has changed since the first MTR, in 2023. At that point, A.I. was little more than a bundle of speculations. We knew that it would change the world, but could barely imagine how. Since then, A.I. has rocketed ahead in reach and sophistication and, marshaled by Silicon Valley, it has metamorphosed into a sweeping arsenal of commercial applications. But what should museums embrace from this new toolkit? This question traced a throughline in our weeklong feast of conversations.

What quickly emerged in our group was an uneasy feeling that A.I., for all its wonders, was barreling down a path that was not, to put it mildly, optimized for cultural institutions.

No one doubts A.I.’s miraculous abilities. Museums would be fools to not tap its potential. Even so, institutions need to think critically about which of these shiny applications they and their audiences really benefit from. In the words of Montreal Museum of Fine Arts director Stéphane Aquin, they must be mindful of the “gap between real and fabricated needs.”

Refik Anadol and András Szántó discussing the use of A.I. in creating art at the 2025 Museums of Tomorrow Roundtable, de Young Museum, San Francisco. Photo courtesy of FAMSF.

Artificial intelligence is already seeping into art museums, as it should. First and foremost, it’s a huge part of culture itself, a palimpsest for new creativity. Museums, especially those showcasing contemporary art, must evolve along with artists as they begin to experiment with these tools, much as they did with photography and video in generations prior.

And there are other opportunities. Museums are an indispensable sense-making apparatus for society. Helping us come to terms with A.I.’s far-reaching implications provides them with a welcome mandate.

At an MTR session at Bloomberg’s offices in San Francisco, a group of startups was invited to showcase pre-market innovations. It was clear from these early-stage presentations just how much A.I. promises to transform museum education, communication, and gallery navigation. Combined with A.R. and V.R., the technology points to new ways of presenting art in physical spaces to diverse audience segments.

As anyone who has summoned ChatGPT knows, A.I.’s research prowess—with all due caveats about hallucinations—is simply transformative. And let’s not forget that the museum is also a workplace. A.I. can and will, for better and for worse, introduce new work streams and efficiencies, creating new kinds of jobs and inevitably menacing old ones. Silicon Valley is certainly working on that.

The Museums of Tomorrow Roundtable 2025. Photo: Gary Sexton.

Pulling back a bit, though, our conversations returned repeatedly to three points that may help frame museums’ responses to A.I.

The first is just how unevenly the blessings of A.I. are distributed across the museum field, nationally and especially globally. While the full ecological and energy impacts of A.I. remain difficult to gauge, we recognize that A.I. systems place significant demands on computational resources and infrastructure, and that, in a global perspective, museums’ ability to access the required hardware, know-how, and even the indispensable electricity is wildly uneven.

Some members of our MTR group work in locales where sustained power outages are frequent and fundamentals of computing infrastructure are simply absent. They reminded us throughout the week that, here as elsewhere, technological innovation may exacerbate, rather than erase, longstanding inequities. If the museum community wants to fully realize the fruits of A.I., advocating with and for cultural institutions in places with weaker infrastructure must be part of this transformation.

Museums of Tomorrow Roundtable 2025 visiting “Kambui Olujumi: North Star” at the San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA. Photo courtesy of FAMSF.

A second insight has to do with the data at the heart of these A.I. applications. Right now, much of what mainstream A.I. makes available to users is based on data scraped from the public web, creating knotty problems around IP and accuracy of information. But what little museums have translated from their holdings, scholarship, and programming into publicly accessible digital assets (most collections are processed in single-digit percentages) remains mostly hidden from view, stored on local networks, accessible only to those working inside institutions.

An enormous trove of museum data has never been stitched together into a larger, cohesive, reliable, and accessible motherlode of art information. Should museums work more actively to blend and harmonize their far-flung datasets? We came to believe this would be essential for our sector, much as it has accelerated other fields, like medicine or finance. Without such comprehensive data, it’s hard to show up at the A.I. party. And without it, the sector as a whole will find it difficult to advocate for museum interests.

In short, as with the emergence of the web three decades ago, A.I. is happening to museums, not with them. To change that dynamic, museums would need to collaborate with each other—and with other players in the art ecosystem, such as universities, galleries, and auction houses—in ways they rarely have.

We asked executives at a leading technology company during the MTR about this dilemma. They told us, in effect, “Don’t worry, just put everything online.” It didn’t strike us as the optimal solution.

Participants at the Museums of Tomorrow Roundtable 2025 on tour at SFMOMA. Photo: Gary Sexton.

The last insight around which our conversations converged has to do with understanding what is and will remain the museum’s superpower in the age of A.I. This may seem philosophical and perhaps even romantic to some, yet it underlies museum strategy writ large.

For all the potentially disruptive applications on display during the MTR, we ended the week on a reassuring note. The more we saw, the more we came to appreciate that the museum—with its singular combination of objects, humans, and architecture—offers something no LLM can substitute.

The museum is a place of experience and gathering, where we can come to terms with our past, present, and future, engage with one another, and understand who we are. Those IRL experiences and human connections are not ready to be outsourced to technology anytime soon. Even as they gear up for the A.I. age, museums are well advised to hone their resources around these fundamentals.

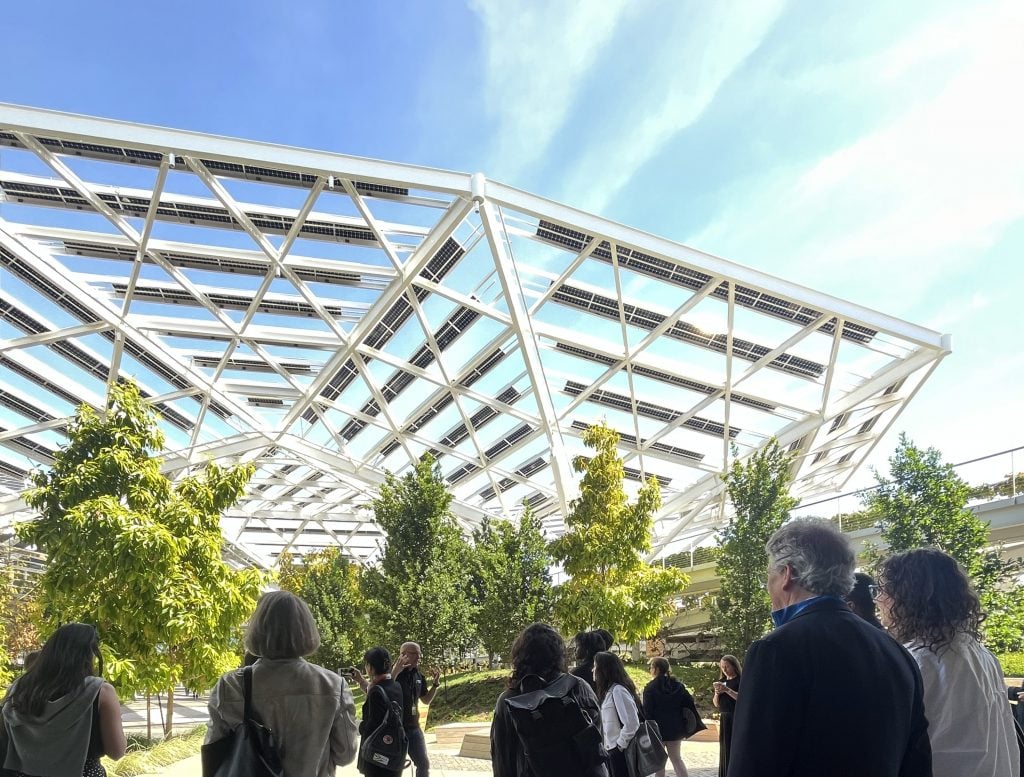

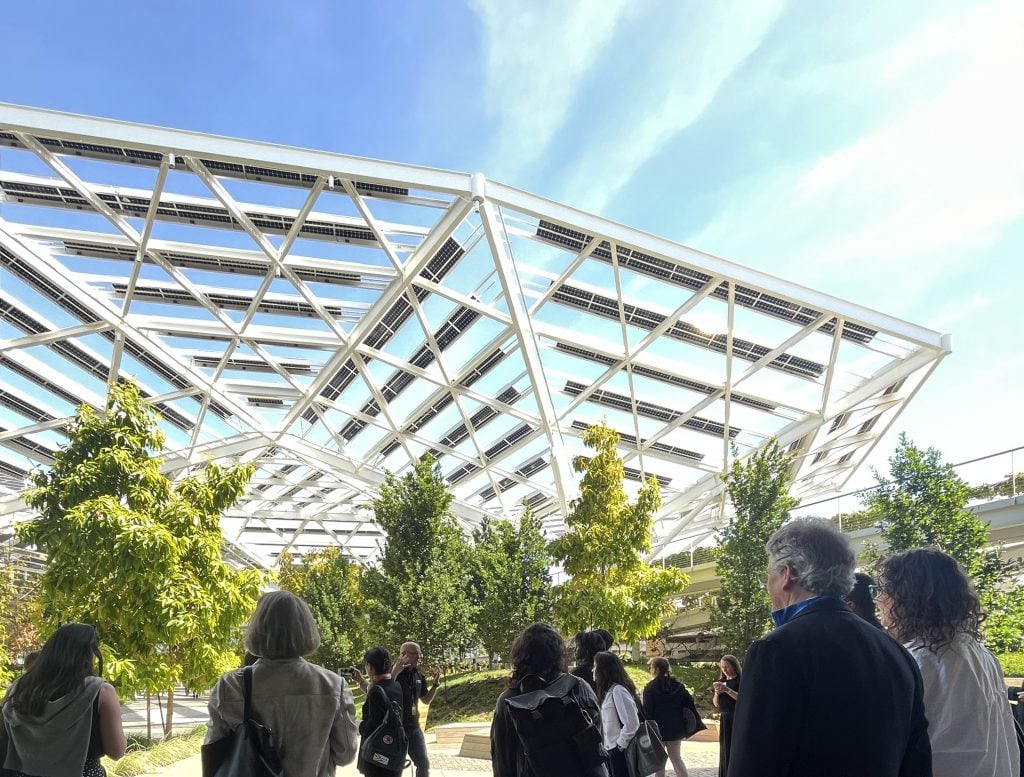

Participants at the Museums of Tomorrow Roundtable 2025, de Young museum, SF. Photo: Gary Sexton.

On the last day of our week, we assembled in a room drenched with sunlight at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center, overlooking a garden filled with sculptures by the likes of Auguste Rodin and Richard Serra. Speaking to us was the musician and computer science professor Ge Wang, who works with students at Stanford at the intersection of artificial intelligence and creativity. He reminded us of the human layers of art and culture that technology cannot touch. As he put it, “design should not exist only in relation to need, but also to humanistic values.”

Reassuring words. Yet we must accept that the values of the art museum will not be encoded into A.I. systems if we stand idly by. If our week in the cradle of the A.I. revolution offered glimpses of a startling future, it also sent signals about the pitfalls of this new technology, and especially of our collective inaction.

Thomas P. Campbell is the director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

András Szántó is the founder of András Szántó LLC and author, most recently, of The Future of the Art World: 38 Dialogues.

Source: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/museums-of-tomorrow-2025-2703585